Stilfserjoch

aka Passo Stelvio

For road cyclists Passo Stelvio is the most

famous, or infamous pass road in the alps. It has

the highest "cult status". When it comes to the

very highest, completely paved roads, this road

comes third after the Cime de la Bonette, which is

not a pass in the classical water divide sense,

and also after Col de l'Iseran by only a few

meters. Some sources disagree. But then life

really has not that much to do with numbers, at

least the interesting aspects of life. The scenery

is what is magnificent, and the way the road

interacts with it, in tunnels and galleries, and

switchbacks, all of which are result of a

turbulent history.

|

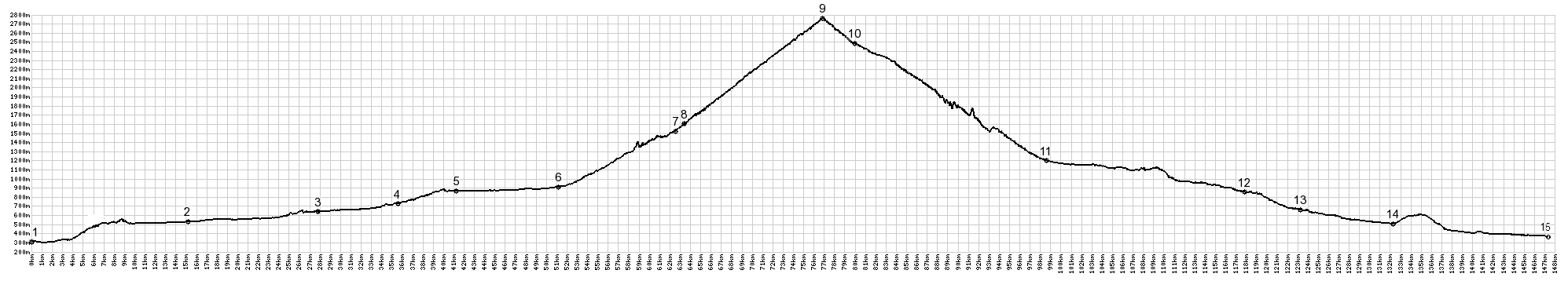

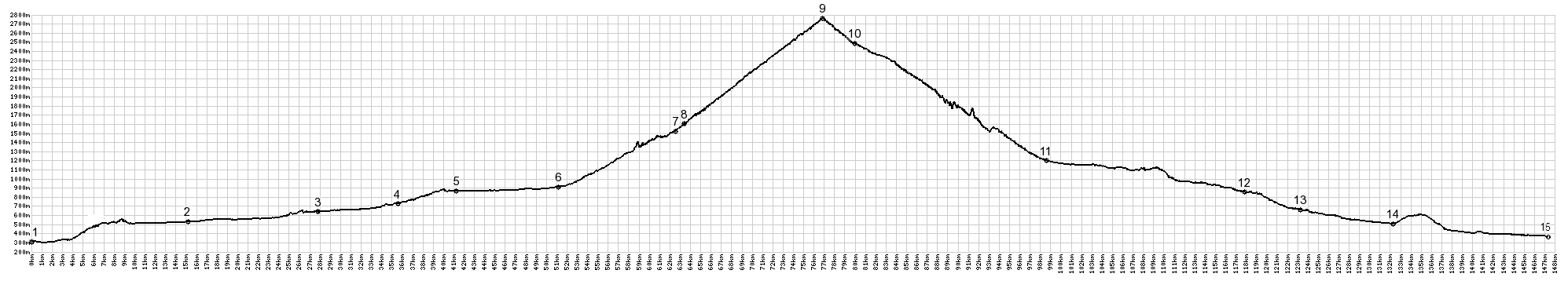

01.(290m,00.0km)

START-END NORTH ALT: Meran

02.(520m,15.2km) Naturns

03.(640m,27.8km) Latsch

04.(740m,35.6km) Schlanders

05.(860m,41.2km) Laas

06.(930m,51.2km) START-END NORTH: Prad am

Stilfserjoch

07.(1520m,62.5km) Trafo

08.(1580m,63.5km) turnoff to Neuwies

09.(2757m,76.8km) TOP: Stilfserjoch

10.(2470m,80.3km) jct with Umbrail Pass

11.(1260m,98.6km) START-END SOUTH: Bormio

12.(860m,117.9km) Sondalo

13.(660m,123.3km) Grosio

14.(520m,132.4km) Lovero

15.(370m,147.2km) START-END SOUTH ALT:

Tresenda

|

Approaches Approaches

From North. (described

upwards) The first part of the elevation profile

is a representative route from Meran to Prad, to

show that there is some elevation gain involved

here. The map does not necessarily follow the bike

path all the way. But there is one, a wonderful

and famous route following the river Etsch.

Most people agree, the real climb up Stilfserjoch

starts in Prad. Exiting Prad, the elite start

their time measurements. I enjoy the view and the

peace. Here it's still just a quiet road through

deep forest. It was early afternoon and the

majority of motorcyclists were still sitting

around consuming food and drink, and when they do

that their motors are turned off, and they don't

make nearly as much noise.

Between the carpet of green leaves, a sliver of a

white wall ahead gives hints of what is to come.

Past the turnoff to Sulden, it becomes clear that

the road is climbing a ridge across from the main

wall in the Ortler Group. Two hotels, solid

rectangular rock boxes, not the stapled together

cardboard housing I am used to, takes advantage of

this green perch across from the white wall. The

switchbacks are numbered, and I wish I had paid

more attention so that I could report their

impressive, staggering number out of own

experience, but in a way it was too many to be

meaningful while trying to get enough energy to

ride up them. Besides, you can look these things

up. There are 48 of them on this side. The first

one stands at 1541 meters near Trafoi, after

exiting some newly built gallery tunnels.

Hours pass and the switchbacks work themselves to

way above treeline. Another large old hotel marks

the first complete view of the final section of zig

zag heaven, the historic stone complex at

Franzenshoehe. The place is switchback 22. 550

meters of climbing over 6.6km distance remain. The

route has now managed to include an overall

direction change into its zig zag squiggles. With

every switchback closer to the summit the scheme

becomes clearer, zig: climb north east, zag: climb

south west but just a little further ... repeat.

Still when the sign next to the stone wall

separating the road from the drop says 5km to the

summit, it just looks like a stone's throw away -

but only a stone thrown form above, which reaches

much further. But then when the sign reads Kehre 1

(switchback 1) it comes as a complete surprise. Some

of the summit buildings visible are actually quite a

ways above the road. The view back down from

switchback 1 is one of the great mountain road

photographs that I have seen in books repeatedly, or

it may have been switchback 2. At this point I

really was tired enough, not to notice the

difference any more.

Slideshow of Northern Approach

From South. (also

described upwards) Again the profile starts much

lower, than where cyclists start their day to

climb this pass: all the way down in the town

Tresenda. Leaving Bormio, there is very little

time to warm up. The road start climbing right

away. Several valleys radiate out from Bormio,

which sits at the hub of several mountain passes.

Opting for Stilfserjoch, you don't see much of

Bagni di Borno, the bath where the nice lady at

the visitor center told me I could have a room for

several hundred euros. Thanks, maybe another time

... in another life.

But after that it gets interesting right away.

The road enters the sheer sided canyon of the

torrente Braulio at half height. Rather than

clinging to the side on a shelf, the road uses a

whole series of galleries and tunnels. During a

morning in June, water is dripping around the

portals like a curtain. On the return, during the

late afternoon of this now hot summer day the

curtains become waterfalls. There are a total of

six of these antique appearing gallery tunnels.

The longest is 250 meters long. All now have

lighting. The lower galleries have a smaller

tunnel diameter, and seem like something

appropriate for a small 1950s Triumph car, for

example.

After this exciting gallery traverse you find

yourself at the bottom of endless zigzags. With a

slope of 12 percent, these 14 switchbacks are the

steepest section on this side and gain 300 meters.

And above that, who knows ? Above the last

switchback only sky is visible. Again an

albergo/ristorante fronts a stream, that becomes a

waterfall during the return. Looking down, while

turning from a zig to a zag, and catching my

breath, the vertical sides along the Torrente

Braulio seem to disappear into the bottomless.

The road now enters a treeless high alpine tundra

valley, the Bocca del Braulio. For now, no more

switchbacks are necessary to climb the grassy

waves. The road passes an old Canton House, a sign

explaining the WW1 situation at this location.

At the junction with Umbrail

Pass sits another old Canton Building, now

closed down, the window shudders painted a vibrant

blue. Its picturesqness derives not only form the

decaying walls, but also that no motorcycles are

parked in front of it. The top of Stelvio and a

few of its old albergos are now plainly visible.

One can gauge the work, that is left to reach

them, surrounded by all that snow. It still seems

to take considerable effort to reach Stilfserjoch

from here. So now is a great time to observe, that

Umbrail Pass, the highest Swiss road pass, is

really only 2km distant, as the crow flies, from

the highest road pass in the alps. Don't think I

have to name it again. - But from down here you

have no idea of the street fair atmosphere waiting

up there.

Past the jct with Umbrial

Pass, the road executes sweeping turns

between peaks and power poles. I want to call it

an industrial wilderness. Focusing between the

powerlines, you can find a world of mountain

vistas in two directions, down beyond Umbrail Pass

and back to where I came from. But - just the

facts please: this last section is 3.5km long and

climbs the last 6 of the total 36 switchbacks on

this side, climbing a mere 200 meters. - Not a

fact: it feels like more.

Finally reaching the top, a small distance before

having a chance to be diverted by the stunning

vista of switchbacks on the other side: Is there

something you would like to buy ? Well maybe not a

stuffed animal, that would be too hard to carry

back down on the bike. But maybe a Stelvio Jersey.

There are probably several hundred to choose from.

- or anything else you can wear, eat, drink, send

in the mail, look at, or put on a shelf.

Apparently there are also a bank, so that access

to money should not be a deterrant for commerce on

Stelvio Pass. And what else would you possibly

want to do in all that grand nature, but visit a

musum of it, the Stelvio Museum on top. To be

fair, if I could or ride up here every week, this

would probably be a wise way to spend my time. But

this time around I didn't see it between all the

other sale items, and sausage sale booths. And to

put things in perspecitve regarding the commerce:

Of course, nobody approaches you and presses you

to make a purchase, like in an Asian street bazar.

This is still civilized Europe. The goods are

there if you want them. Some do, some don't.

Slideshow of Southern Approach

A final note, as a reminder to myself, since I

forget things so easily ... about timing: As is

often the case, cyclists and motorcyclists often

have the same geographic goals, even if their

goals in life in other aspect don't intersect that

much. I had the absolute perfect weather on my

ride, and so did the thousands of motorcyclists.

Even if I picked the right weather (actually it

picked me), I picked a bad time, or date: the

Pentecostal holliday in northern Europe, when

thousands of motorcyclists (but certainly not all,

that would be hundreds of thousands) celebrate the

resurrection of Christ by seeing how close they

can come to death, or at least make enough noise

with their engines, to scare away life any with

funtioning ears. It was an internationally

occupied road. But I noticed a few differences.

Their were motorcycles from Belgium, the most from

Germany, lots from Austria. The ones with the

girls on the back, their butts hanging over the

back of the bike like a gothic Christmas tree

ornament, were at least 90 percent on Italian

bikes. I guess those were the local day trippers.

There was also a very small contingent of motor

cyclists with an american look to it. The bikes

with the handlebars so high, the riders look like

they are trying to do pullups, but can't because

... of a number of factors.

Historical Notes

In some books it is written, that this pass was

used in the bronze to get goods from Tyrol to

Italy. But it seems obvious that Umbrail Pass was a

much easier, therefore and more often used

crossing.

In the early 19th century Italy did not exist as a

country. Instead a small group of European

imperialist types parceled out the continent

between themselves. Historically this is known as

the Congress of Vienna at the end of the

Napoleonic Wars. The northern end of today's

Italy, Lombardia with Milano as its capital, was

given to the Hapsburg family, who ruled the

Austro-Hungarian Empire. In order to connect this

part of Lombardia with the rest of their empire,

they wanted (or needed) this road, which does not

stray into Switzerland, as Umbrail Pass does.

After years of unsuccessful attempts, they

finished a road across the pass in 1825. This gave

them a clear line of transport from Austria into

the dolomites up into the Val Venosta and

Valtellina areas.

In the 1860s Italy managed to unite and gain

independence. The top of the pass was now the

border between Austria and Italy. During WW1

Italian soldiers confronted Austrian soldiers over

a distance of 50km, stretching along the ridge

line between Passo

Gavia and Stilfserjoch. Signs along the road

on the Bocca di Braulio point out the

strategically most important peak in the Stelvio

area: Monte Scarluzzo (3091m). It was taken by

Austrians and stayed under their control until the

end of the war. Today the trenches, paths and

tunnels make hiking destinations.

But then, before WW2, Hitler gave German speaking

South Tirol to Italy, as part of the allegiance

between the two allies. Suddenly both sides of the

pass were now Italian. (Are there any other

European passes that have such a turbulent

national history ?) This eliminated the original

purpose, for which the pass was constructed, and

its importance diminished. Prior to this event,

there was a period when the pass was kept open

year round. This period ended once and for all.

The road was paved in 1938, and for a time was

regarded as the highest paved pass in the alps.

Many people believe that this is still true.

Nowadays there are several passes in this range,

where the difference in elevation falls within the

margin of error: Col

d'L'Iseran (2770m) in 14m higher, Col de

Agnel (2744m) 13m lower. Col de Restefond

with 2715m is actually 42 meters lower. But you

can argue, that starting at sea level on the

Mediterranean it has by far the biggest elevation

gain. There is also an additional loop on top of

Col de Restefond, called Cime de la Bonnette, that

makes it up to 2802m, that is 45m higher. But this

is not a recognized pass, but instead a scenic

loop road. Expanding the view beyond the alps to

all of Europe, there is also a higher paved out

and back road to the Pico Veleta area in the

Spanish Sierra Nevada which reaches a much higher

elevation.

Cycling: Fausto Coppi was the first to

get to the top of the pass as part of the Giro

d"italia in 1953. In 1961 the race went over the

top and finished in Bormio, won by Charly Gaul.

More often than not, the race finish has been held

on top of the mountain.

In 1956 and 1972 and 2012, the Giro went up the

Bormio side of the pass, and through all its

tunnels and galleries. Surprisingly, this is one

of the few slopes where the descent has often been

more instrumental in deciding who gets across the

finish line first.

You might expect that cancellation of a stage like

this is a major risk, and you would be right, 1988

because of snow

Dayride

PAVED/ VERY SHORT SECTION UNPAVED

Stilfserjoch, Umbrail

Pass: Bormio > Bagni di Bormio >

Umbrail Pass > Sta Maria > Taufers > Prad

> Stilfserjoch > back to Bormio: 67.7miles

with 10442ft of climbing in 6:56hrs (Garmin

etrex30 m4:14.6.8)

Notes: this measured 64.0 miles with 10008ft of

climbing in 6:40hrs using the VDO MC1.0 with

wheelsize set to 79.8i

The last day with different start and end

points on this tour was: Passo Gavia

top left: some

of the the switchbacks from below look a bit

like the buttresses to a gothic churchbr>

bottom: the view from inside one of the old

and narrow gallery tunnels

|